The Serpent and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil - The Concept of Forbidden Knowledge

Old Testament / Mythology

In the most distant and remote past, I went on a scholarly voyage out to identify the origin and identification of the biblical nachash or serpent found in chapter 3 of the Book of Genesis. This is the point at which I came across the myth of Adapa. I was directed towards the Mesopotamian fertility deity that went by the title of Ningishzida, and sometimes Gishzida. The name is believed to translate to ‘Lord of the Good Tree’ or ‘Lord of the Trusty Timber’; Gishzida translating to ‘Good Tree’ or ‘Trusty Timber.’ In the Sumerian poem The Death of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh meets Ningishzida along with Dumuzi in the Underworld. [1] Babylonian incantations have also named Ningishzida as a guardian over the demons that dwell in the Underworld. His name has also been mentioned in laments over the death of Dumuzi. In the myth of Adapa, Adapa encounters both Dumuzi and Gishzida guarding the gate to the Heaven of Anu, the highest heaven. [2] The story begins with Ea giving Adapa eternal wisdom but not eternal life. It is already clear to the reader that this wisdom was a feature reserved strictly for the gods. So one day, Adapa ventures off into the “broad sea” in his boat so he can go fishing for the house of his lord, Ea; and without a rudder, his boat went adrift. Adapa threatens the South Wind for sending him adrift and informs him that he will break its wing, and proceeds to do so. Angry, Anu discovers the actions taken by Adapa and calls for Adapa to stand before him in front of his council at heaven. Aware of “heaven’s ways”, Ea warned Adapa with the following instructions:

‘Adapa, you are to go before king Anu.

You will go up to heaven,

And when you go up to heaven,

When you approach the Gate of Anu,

Dumuzi and Gishzida will be standing in the Gate of Anu,

Will see you, will keep asking you questions,

“Young man, on whose behalf do you look like this?

On whose behalf do you wear mourning garb?”(Adapa has to answer the following)

“Two gods have vanished from our country,

And that is why I am behaving like this.”(The two will continue to ask)

“Who are the two gods that have vanished from the country?”

(Adapa has to answer the following)

“They are Dumuzi and Gishzida.”

They will look at each other and laugh a lot,

Will speak a word in your favor to Anu,

Will present you to Anu in a good mood.

When you stand before Anu

They will hold out for you bread of death, so you must not eat.

They will hold out for you water of death, so you must not drink.

They will hold out a garment for you; so put it on.

They will hold out oil for you; so anoint yourself.

You must not neglect the instructions I have given you.

Keep to the words that I have told you.’

The time came where Adapa went to heaven and stood before Anu. Everything was going according to what Ea had warned Adapa about. Adapa won favor with both Dumuzi and Gishzida, and Anu proceeded to ask him for the reason of his breaking of the South Wind’s wing. Adapa relates to Anu the entire story, while in the meantime both Dumuzi and Gishzida spoke in Adapa’s favor to Anu. After hearing Adapa’s response, Anu was not favorable to the idea that Ea had given mankind wisdom, “the ways of heaven and earth”, and asked himself, “What can we do for him?” because as mentioned before, wisdom was a quality for the gods to have and not mankind. The story finishes off with Anu requesting for someone to fetch him the bread and drink of eternal life, but Adapa did not eat or drink; also a garment which Adapa put on; and oil which Adapa used to anoint himself. Anu, watching and laughing at Adapa’s actions, asked him why he didn’t want to be immortal. Adapa answered:

‘(But) Ea my lord told me: “You mustn’t eat! You mustn’t drink!”

Adapa was then sent back to the earth, and the story ends with a few fragmentary lines. The story shows a lot of similarities to the Genesis account. First of all, in the Genesis story, YHWH forbids both Adam and Eve to eat from both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, while in the Adapa narrative, Ea forbids Adapa to eat and drink the bread and water of life, giving Adapa the opportunity to be immortal like the gods. Second is the serpent figure in Genesis, while we have a similar deity in the story of Adapa involved with the offering of eternal life to Adapa. Last is the idea that wisdom was reserved for the gods, and no mortal shall have it. Both narratives stress the point that man can neither have nor handle this acquired knowledge.

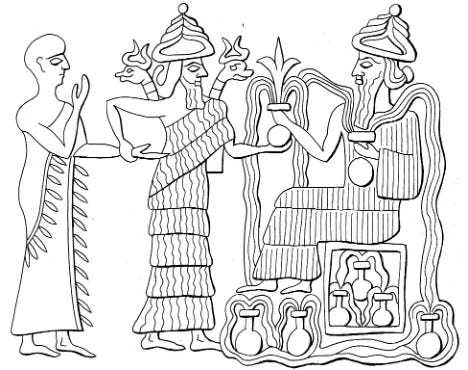

Many scholars are still unclear about the exact meaning of this story. Did Ea deliberately trick Adapa out of immortality, or was he really trying to help him? Did Adapa defy (unwritten) laws of hospitality when he refused both the food and drink of life in heaven, which in turn caused Anu to punish him? [3] Another point of major interest with one of these deities resides in the fact that its symbol was the horned snake or dragon. An image of a cylinder seal impression has revealed that Gudea, the Sumerian ruler of Lagash, regarded Ningishzida as a personal protective deity and recorded a dream where he appeared to him. On this impression is also an image of Ningishzida, who has two horned serpents, sprouting one on each shoulder.

But what of the Sacred Trees?

Throughout the Levant and Mesopotamia, scattered, we find references to sacred trees in both imagery and literature. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero Gilgamesh is on his quest to find immortality in a plant of life in the far-off reaches of what may have been Dilmun. The Ugaritic-Canaanite Asherah and the later Phoenician/ Carthaginian equivalent Tanit were always represented in the form of trees, and symbolized both wisdom and life. Tanit translates to ‘Lady Serpent.’ In her imagery, she is seen represented as the tree of life while flanked by caducei on both sides. A caduceus is a representation of a staff with two entwined snakes. This may hint at a close relationship between the tree of life and snakes. Asherah was the consort of El and the principle goddess of both Sidon and Tyre. She is known to also be identified with the goddess Astarte. Asherah is the ‘Mother of the Gods’, and her name is thought to have originally been pronounced Athirat. [4] She is also called Elat (a feminine form of El). Asherah, the ‘creator of creatures’ and mother of the gods, was frequently seen in the position of the tree of life, giving sustenance to the animals at her sides.

In the Hebrew language and lore, the term ashara literally translated to ‘sacred tree.’ Expanding on this, the ashara was a small votive column or even a post of wood meant to evoke the sacred groves or wooded temple precincts that adjoined various fertility cults in the Near East, such as that of Astarte at Afqa. [5] Symbols such as this marked the site or presence of the divinity within that region.

Reliefs dating to the Neo-Assyrian period emphasized the great cultural importance of the sacred tree (or the Tree of Life). Actually, most of the images found today date to the Neo-Assyrian period, such as one found at Fort Shalmaneser (8th century BCE), where a Phoenician-made ivory panel depicts the king in his role as protector of the Tree of Life. Many other reliefs date to the same period in time, some of which can be found at Kalhu at the palace of Asshurnasirpal II. Situated behind the king’s throne, the relief shows the king on both sides of the tree, above which, in the winged disc, is the Neo-Assyrian head deity, Ashur; and behind the king (once again on both sides) were winged sages. Could all of this have influenced later Hebrew tradition emphasizing the importance of the sacred trees in Genesis?

Feature image: Ashurnasirpal II flanking both sides of the Sacred Tree (close-up). (Nick Thompson / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Notes

[1] Dumuzi (biblical Tammuz) was a shepherd god. He had strong cults stationed throughout the Near Eastern world. Many narratives exist with him from Mesopotamia (i.e. Innana’s Descent to the Underworld, Adapa, etc.) to the Old Testament (i.e. Ezekiel).

[2] The apkallu are antediluvian sages who traveled to heaven. Adapa was the son of Ea, a priest in Eridu. Also known as Uan (Oannes of Berossos), the first of the Seven Sages, who brought the arts and skills of civilization to mankind.

[3] A piece of text known as Fragment D is thought to hold an alternate ending to the narrative concerning Adapa. It is followed by an incantation against disease, invoking Adapa. This ending is questionable.

[4] ’atrt—Athirat is the Ugaritic name for the Hebrew Asherah.

[5] Deu. 16:21.

What is in the metal hand bags of every ancient culture . DNA? Genetic material? A battery? I see the ancient drawings with two men facing the tree of life sometimes with pine cones. Are they Seeding the planet? What do the handbags represent and what is inside them in carvings in every continent?

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing this!